Into the Woods (2014)

Director: Rob Marshall

Writer(s): James Lapine, Stephen Sondheim

Starring: Meryl Streep, Emily Blunt, Anna Kendrick

Disney's Into the Woods is DISNEY'S Into the Woods. That could be a review in and of itself.

OK, a little more context is necessary. If one could not tell from Rodgers and Hammersmonth, I'm a bit of a musical theatre nut. To an even greater degree, I'm a movie musical nut. I consider the musical to be a form of film as important to its development as is the tragicomedy to stage plays or as the bildungsroman is to novels. I'm also very much a traditionalist in this route: I want dance numbers with artistry in mind, I want voices with natural vibrato and ring, I want consistent set pieces. But, ever since 2002's Chicago, the movie musical has taken a rather dark turn, in my book. Unless original Disney animation is involved, movie musicals have become stage musicals trimmed back with no thought to theme, pacing, or character development. They are, as Roger Ebert once put it, "songs connected by a story" instead of "story connected by songs." Into the Woods is another film right down that line, and it's one of the most disappointing movie going experiences I've had this year. A great deal of my rage comes from my feelings towards the original and the flaws of adaptation, but there are too many flaws in this movie to give it a pass.

Into the Woods is mostly a combination of the stories of "Jack and the Beanstalk" and "Cinderella." A witch casts a curse of infertility upon a baker and his wife after the baker's father steals some of her magic beans. In order to get the curse lifted, the baker and his wife need to retrieve "a cow as white as milk, a cape as red as blood, hair as yellow as corn, and a shoe as pure as gold." Along the way, the baker and his wife encounter Little Red Riding Hood, Jack, Cinderella, and the respective side characters from each story. By the end of the musical's first act (the film's first hour and a quarter), they manage to get the curse lifted. Yet, in the second act, the wife of Jack's giant, killed in the first act, comes down to wreak vengeance upon the characters of the story. Many fairytale characters who normally end up living "happily ever afters" end up dead. It soon falls to the baker, his wife, Jack, Little Red Riding Hood, and Cinderella to kill the giant or turn on each other in a morally ambiguous plot.

The narrative of Into the Woods is incredibly intricate but very easy to follow, in both the film and the original Sondheim musical. Fans of the original will note that many, many elements from the original musical have been cut or altered, nearly all of which are to the film's detriment. Some characters who die in the musical do not die in the film, crushing the opportunities for character development and theming that result from these deaths. Perhaps the biggest and most devastating change is the substitution of the baker for the narrator, who is a character in the original musical; while this seems like a minor change, it drastically reduces Into the Woods's impact as an incisive criticism of determinism and fairy tales as fate. I'll discuss this in greater detail, but the narrator's importance to Into the Woods cannot be understated. In many ways, it is essential to understanding just what makes the original show so great. At the basest level, Into the Woods remains coherent and focused with the cuts, even if it loses much of its depth.

I'll try to be more objective and discuss exactly what Into the Woods gets right. For one, the sound mixing is excellent; the instruments are perfectly set to complement the vocals. While this should be an obvious thing to do, I've seen more than a few movie musicals fail to keep their dynamics in check. The costume design is also spectacular. The cinematography is quite nice in many scenes. The film looks fantastic; the little bits of color shading really make everything pop. This is what Into the Woods needed to be, visually. By far the best element of the film is Emily Blunt as the Baker's Wife. She is the one performer in the show who goes above and beyond the call of the libretto and gives us more than what we are looking for. Her confidence in both her maternity and her sexuality lends her part a real credibility that's lacking in most of the other performances. Her comedy is great. She is a joy every second she is on the screen. Also good are Johnny Depp and Chris Pine as the lecherous Big Bad Wolf and Prince Charming, respectively; they might chew the scenery a bit much, but the roles call for it. Daniel Huttlestone is a half-decent Jack as well.

Then there's the bad.

James Cordren is a likeable actor in most everything he is in, but likeability alone is not enough to give his performance as the Baker a pass. The Baker's character needs to struggle morally throughout the show in order to be compelling, and Cordren is not an accomplished enough actor to make the part work. I never believed that he was going through any turmoil, even when he suffers the worst trauma in the show. Lilla Crawford initially displays the innocence needed for Little Red Riding Hood, but she is unable to develop the character any further in the second act. Her "pouty" face is not enough to express the character's sense of growth. Anna Kendrick, one of my personal least favorite actresses, never fails to disappoint me with disappointment; her face is as expressionless as ever, and her singing is awful (she closes the diphthong every time). Her face is blank whenever the camera isn't holding her on close-up, and it seems as if she is totally oblivious to what is going on around her.

Most disappointing of all is Meryl Streep as the Witch. Regardless of how one interprets the character of the Witch in the original show (for the record, I consider the Witch to be Sondheim's critique of exactitude and utilitarianism), one thing is clear: the Witch is certain of her identity. Throughout the movie, I had a very difficult time pinning the Witch down to a clear character due to the spastic, over-the-top nature of Streep's performance. Ham can work in a performance (look at Christopher Walken), but an identity must clearly exist for it to work. Streep's Witch is so inconsistent in what she's trying to be - the apathetic monster of fairytale lore, the over-doting mother, the diva, the utilitarian, the comedienne - that she ends up being nothing. Streep may be giving her all, but there's no role into which she can give it. Thus, she ends up being the cast's weakest link in spite of her being the best actress in the movie.

I find it difficult to pin down the worst part of the movie, as my voice as a musical theatre fan conflicts with my voice as a pure movie critic. Thus, there are two things that emerge as Into the Woods's biggest flaw. The more obvious, movie critic, complaint is that of the terrible pacing. In the original musical, the two acts of the story act as tonally contrasting pieces, one of which is generally lighthearted, one of which is generally dark. The film fails to transition between these two parts; the shift is very abrupt. It's especially agonizing considering how easy a fix could have been made. Into the Woods should have done what most of the great movie musicals - The Sound of Music, Fiddler on the Roof, Carousel - have done and put an intermission card in the middle of the show. This would have prepared the viewers for the change in tone. Sure, it might come as a shock to the modern, Facebook-loving, immediate access audience, but it's the easiest and best solution to the problem at hand.

As a theatre-lover, there's an even bigger sin at work. Into the Woods is heavily reliant on pitch correction and musical simplification in order to make its performers' singing palatable. If one pays attention, one will realize that every singer comes in exactly on the pitch. Never is there an alteration to the vowel or intonation in order to tune the note, for even a fraction of a second, as is the case with 99% of all singers. Furthermore, the vibrato for everyone's voice is remarkably reedy and artificially produced. Never do the notes ring in the ear, unless obvious echo effects are used. Perhaps even more insulting is the alteration of rhythms and registers in order to make the score easier to sing. The score is butchered, with syncopations and triplets removed almost entirely. Whenever a part becomes too difficult for a performer to sing, usually James Cordren, the singers flip down a register in order to sing the part. This would never fly in a play; in fact, any alteration to Sondheim and Lapine's score is viable to get a production company sued for violating copyright law. Worst of all, with all the pitch cheating, I mean, correction and musical alterations, Anna Kendrick still sounds awful.

In the broad scheme of things, poor casting, pacing, and musical execution cannot completely ruin a movie (though they can prove taxing). Is the film at least focused? Overall, yes. Into the Woods tells a complete story and manage to fulfill the basics of the original musical. Yet it very much feels like a SparkNotes version of the show. Of all the main themes of the show - the futility of determinism, the complexities of raising a child, the nature of causality in a post-Tolstoy world, the voyeuristic nature of male sexuality - the Disney adaptation fully develops only the last (surprising, considering that this is Disney). As far as being a fairy tale satire, the only point the Disney adaptation manages to make is, "sometimes happily ever after doesn't happen." Roll the end credits.

In my book, this is the worst insult one could give to the original musical. All fairy tales have a finality and certainty to them that Sondheim and Lapine clearly find disingenuous. It doesn't matter what happens along the way, be it the blinding of stepsisters or the death of a giantess's husband; the heroes get a happily ever after and all is done. Life doesn't work out this way, and no matter how poignant the morals of fairy tales might be, their clear-cut endings thwart any questions we might have about them. By killing the narrator and destroying the internal path of the the woods in the original musical, Sondheim and Lapine force both the characters and the audience to face a world in which there aren't just ambiguous endings: there are ambiguous choices, ambiguous characters, ambiguous environments. The world of Into the Woods is meant to be complex. While Emily Blunt does her best to communicate this point in her admittedly great rendition of "Moments in the Woods," it's just not enough to compensate for how much Disney cuts from the film in order to truncate the themes. It's too certain.

Thus, as far as adaptation is concerned, Disney's Into the Woods is a flat-out flop. It doesn't manage to communicate the complexities of the original; it's instead a mostly rushed, mostly subpar, mostly squeaky clean version of the stage show that looks really nice. The movie critic in me hopes, that if both the narrator and an intermission were included, this could have been one of the great movie musicals, especially considering that this show comes from Disney. The theatre nerd in me tells me to scrap everything and restart with an entirely new cast of singers who can act rather than actors who can sing... with help from the studio heads. As it is, Into the Woods is just OK, instead of being good, bad, or great. This show deserves better.

Recommendation: If you love the original show and are not certain as to whether or not you want to see the Disney adaptation, stay away. If one has never seen the show before, do not see this musical; rent instead the original 1991 stage recording and appreciate the full-length, uncut brilliance of the original cast. If you've seen the show and want to see Emily Blunt redeem herself from her lackluster performance in Edge of Tomorrow, then go ahead and see Into the Woods. As for anyone else, there are too many good movies out right now to spend money on this one. Go see Birdman instead.

I give Into the Woods 4.6/10 stars.

Friday, December 26, 2014

Thursday, December 25, 2014

The Top Twenty Greatest Christmas Songs Ever Written

There are dozens of sticks in the mud who hate Christmas music for never changing, but I am most definitely not one of them. Sure, I have those Christmas songs that I loathe ("Last Christmas," "The 12 Days of Christmas," "All I Want for Christmas Is You"), but I actually like the vast majority of songs that dominate the holiday airwaves. It doesn't matter if it's a Christian traditional, a 1940s standard, or a new rock and roll classic: if it's a Christmas song, I probably like it to some extent or another. The following top twenty is my ranking of the twenty best Christmas songs ever written. I judged these songs, more or less, by how well they fit the attitude of the season, the quality of their composition, their importance in the holiday canon, and the depth of the "fuzzy feeling" I get whenever I hear them. I'm trying to be objective in my ranking, so some of my personal favorites like "Christmas Time Is Here" and "Santa Claus is Comin' To Town" didn't make the list. I also didn't include any songs/arias from Handel's Messiah, as they don't quite fit the spirit of the list. Without further ado, my top twenty greatest Christmas songs.

20. "Rockin' Around the Christmas Tree" - Johnny Marks

I think "Rockin' Around the Christmas" is the Johnny Marks song that has held up the best, and it's the best Christmas song to come out of the original rock and roll era. "Jingle Bell Rock" is also fondly remembered, but I think "Rockin' Around the Christmas Tree" has held up just a bit better. The guitar twang is cleaner and more memorable, especially with rock guitar legend Hank Garland plucking the strings on the 1960 original. Plus, "Jingle Bell Rock" doesn't have the best saxophone solo in Christmas history: one can thank Boots Randolph, more famous for his work on "Yakety Sax." It's also the song on which Brenda Lee actually sounds her best, as opposed to all her of her non-holiday tunes. It's a fun song with a great beat, and it certainly gets one into the partying spirit of the holiday.

19. "Adeste Fideles/O Come All Ye Faithful" - Traditional

The actual authorship of "Adeste Fideles" is actually unknown. It is most commonly attributed to the 18th century composer, John Francis Wade, but other composers, from Handel to Gluck, have also been suggested authors. What certainly is apparent is "O Come All Ye Faithful"'s critical standing in the sacred Christmas song canon. One of the most universally loved sacred songs, "O Come All Ye Faithful" is one of the best "gathering" songs for any Christmas Mass, what with its warm tones and embracing music welcoming any person to a holy gathering.

From its subtle harmonic sequencing to its spectacular dynamic, "O Come All Ye Faithful" is a marvel of composition in every respect. Few songs better accentuate the glory of Christmas, in the religious sense, at least. Even if one isn't religious, one can still appreciate just how massive this song is. There's a spiritual depth to "O Come All Ye Faithful" that is truly hard to match. It's just a bit too boisterous to get any higher on the list, as I feel Christmas gains all the more value in exploring the interplay between community in the large and small sense. "O Come All Ye Faithful" seems to only focus on the former. Other Christmas hymns do a better job of accentuating them both.

18. "Little Saint Nick"- The Beach Boys

The key to "Little Saint Nick" is the quality of the production. As usual, Brian Wilson arranges an excellent mix on the vocals, accentuating all the right parts at all the right times. There's such a real sense of balance on the sound that is very absent on most other contemporary Christmas songs. The xylophone offers a classic Buddy Holly-esque sound while the piano offers the surfing feel of the Beach Boys' original songs; both feelings produce a Christmas song that is both unique and timeless. This is a Christmas song so good that no cover ever quite does the original justice. "Little Saint Nick" is one of the great Christmas records, one that will not be going away anytime soon.

17. "Es ist ein Ros entsprungen/Lo, How a Rose E'er Blooming" - Traditional

"Lo, How a Rose E'er Blooming" is very much an expanded metaphor of the birth of Jesus Christ, with the baby boy likened to a blooming flower. The lyrics blend perfectly with the almost chilly harmonic rhythm of the piece, creating a truly beautiful effect. The element of the hymn I find the most interesting is its color: unlike with most other songs, I can vividly get a sense of color from listening to "Lo, How a Rose E'er Blooming": the faintest amount of red in a pure white canvas. When a song can affect a person on a complete aesthetic level, at least something has been done right. "Es ist ein Ros entsprungen" is a Christmas classic in every conceivable way, a flower that has endured for centuries.

16. "Happy Xmas (War Is Over)" - John Lennon

"Happy Xmas" seems to have two narrators. The first, John, is a critic of the world inveighing against the injustice and hypocrisy of the world around him; this narrator is truly biting, with an almost contemptuous attitude towards global leaders and the listener. The second, Yoko and the children's choir, is the ever-hopeful crowd, simply chanting for peace; in another interpretation, this voice is the blithely unaware Christmas mass public. I tend to side with the former, as the line "let's hope it's a good one without any fear" suggests hope for a peaceful world to come. In any case, the interplay between the two narrators creates a truly powerful protest song.

While a great song in its own right, "Happy Xmas (War Is Over)" can't get any higher on this list due to its nature as a protest song. It's a great song; it's just not essential to the holiday.

15. "It Came Upon a Midnight Clear"- Edmund Sears and Richard Storrs Willis

I think "It Came Upon a Midnight Clear" is the best of the angel-focused Christmas songs. In all honesty, both "Angels We Have Heard on High" and "Hark, the Herald Angels Sing!" are the same song (same chord progression, same phrasal climax, same length). Also, "It Came Upon a Midnight Clear" doesn't try to over-awe the audience. It creates a warm presence as opposed to an awe-inspiring presence. Fitting in the overall spirit of the New Testament, I think it's much more tonally appropriate. "It Came Upon a Midnight Clear" is a wintery tune with a spiritual edge that makes it one of the great traditional Christmas carols.

14. "Fairytale of New York" - The Pogues feat. Kirsty McColl

"Fairytale of New York" has two sections. The first is a rather morose love letter, describing an old drunk's last Christmas alive and the depression of the love-sick lead singer. The second part is a rollicking jig-inspired tale of a Christmas romance. The interplay between the Pogues' lead singer, Shane MacGowan, and guest singer Kirsty McColl in this portion is really fantastic. It's actually incredibly funny, with the two spouting insincere insults at each other in a pseudo-romantic banter. The excellent orchestration really produces the feeling of Christmas in New York.

"Fairytale of New York" is a practically perfect song, but it's lower on the list because it's "a Christmas story" rather than "the Christmas story" or "all Christmas stories." It's so incredibly specific as to crush the universality of the holiday. The next few songs are even better at capturing the Christmas spirit.

13. "Carol of the Bells" - Mykola Leontovych

I'd also like to address the famous and/or "infamous" (depending on the audience) Trans-Siberian Orchestra version of this song. For those who haven't heard it (somehow), the Trans-Siberian Orchestra turned this relatively simple choral song into a three minute heavy metal Christmas opus. The piece undeniably feels as if it belongs in the final boss battle of a JRPG rather than a Christmas setting, especially with the simplification of the melodic build to 12 ostinato repetitions as opposed to the traditional 20. Nonetheless, I still think it's enjoyable in its own right. I think overly praising it or overly hating it tends to miss the point of it: it's not aspiring to be a Christmas song; it's aspiring to be a heavy metal song. In that right, it succeeds.

Be it the song that the local choir sings every year or the song that every local high school band learns how to play, "Carol of the Bells" is a holiday staple that is as threatening as it is beautiful.

12. "Sleigh Ride" - Leroy Anderson

I'm kind of cheating on this one, as "Sleigh Ride" is neither a Christmas song nor a song in and of itself. The original Leroy Anderson composition and the definitive version of the piece is an orchestral work; if there isn't singing in it, it's not a song. At the same time, "Sleigh Ride" has since been adapted into a song that works well enough in its own right and that is improved considerably in light of the sheer quality of the original piece. It may not be explicitly be about the holiday, but it has a wintery feel, what with the sleigh bells and the slapstick, that just screams Christmas. It's a song that alludes to the secular community of the holiday.

Of the vocal versions, my favorite version probably comes from the Ronettes. I'm just a sucker for Phil Spector's Wall of Sound. Not to mention, the backing vocals really do enhance the tone of the piece, suggesting the instrumental original. Instead of "Walking in the Rain," one feels as if one is "riding in the snow." There are plenty of great cues in the instrumentation in this version, especially the string breakdown in the song's middle. It might not have the bridge of the original, but it's great all the same.

If there was any one problem with "Sleigh Ride," it's the lack of sing-along appeal. I can really only picture one person singing "Sleigh Ride" at a time, and most choral arrangements of this piece tend not to do it justice. And, overall, I tend to prefer the instrumental, non-song version of the piece. As it stands, "Sleigh Ride" is one of the best pieces of Christmas music, even if it's not the best single "song" of the holiday.

11. "Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)" - Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry

For this Christmas song, I think there are two equally definitive versions out there. The first is, of course, the Darlene Love original, right from the A Christmas Gift for You album, in my opinion the greatest Christmas album ever made. This is definitely the version with the best production, what with the excellent appropriation of the Wall of Sound, with the bells tolling at the perfect times to create a beautifully mournful song. Throw in the best singer of Phil Spector's regular collaborators, Darlene Love, and one's got a classic song. The other excellent version belongs to U2; Bono adds an incredible pathos to this song, with his excellent vocals really hitting this song out of the park. The Edge offers a rather subdued performance, actually recreating the sombre yet upbeat feel of the original.

All the same, most versions of "Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)" are good. The recent Michael Bublé version just gets better and better the more I hear it, and even the Mariah Carey version holds up to a few listens. "Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)" is a bit of Christmas misery that's the perfect red pill to the Christmas experience.

10. "I'll Be Home for Christmas" - Walter Kent and Kim Gannon

If one has a relative who is or has served in the armed forces, "I'll Be Home for Christmas" is more than likely a favorite, if not the favorite, Christmas song of the season. A song offering hope for a safe journey home, "I'll Be Home for Christmas" was written with soldiers in mind. The Bing Crosby original is a true holiday classic that will never fade. I think the recent version by Josh Groban is actually just as good, whether or not one includes the audio recordings of American servicemen and women. It's a song so powerful as to be effective with any singer.

For me, "I'll Be Home for Christmas" offers even more than just connection between families torn apart by distance. To me, "I'll Be Home for Christmas" also provides a spiritual connection between those alive and dead. Be it my Christianity showing or my personal hope for something beyond our lifespan, there's a deeply spiritual family connection that is inherent to "I'll Be Home for Christmas." When hearing it, I feel as if connected to my whole family at once. Perhaps it's just one college student's wishful thinking, but this song manages to connect on every level. If this were a purely personal list, this would have ranked higher, but there are a few other songs that I think are even more emblematic of the holiday.

9. "River" - Joni Mitchell

Of all the songs on this list, "River" is the song least associated with the season. In my opinion, however, the Christmas song canon is not truly complete unless one considers the mournful majesty of "River," the only Christmas song that has ever managed to encapsulate absolute misery. Certainly, "Fairytale of New York" and "Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)" are rather "sad" songs as compared to most Christmas tunes, but "River" is one of the saddest songs ever written, period. It's one of the best songs off of Joni Mitchell's exemplary Blue album, and, while extremely secular, it has much more to do with Christmas than many songs that name drop Christmas in every other line.

"River" begins by quoting the main motif of "Jingle Bells," quite possibly the happiest and most inane Christmas song of them all. Yet the harmonic progression of the piece transforms the "Jingle Bell" motif into something truly morose. The lyrical sentiment matches that of the far more famous "White Christmas," yet, once again, the theme is turned on its head, with the dreams of snow becoming dreams of ice and pain. There's plenty of ambiguity to the lyric: does Joni want to fly away from her problems, fly away from the commercialization of Christmas, fly away from her misery? There's plenty of room for interpretation.

It gives me pride to see "River" becoming more and more of a modern classic, what with dozens of artists covering it around the holiday season. In all honesty, more radio stations should play "River" in rotation with the other Christmas tunes. After all, instead of having weak-willed people well up to the shameless pandering of Newsong's "The Christmas Shoes," we can all cry to a Christmas song that is genuinely heartbreaking. "River" is the story of the world's most miserable Christmas, and it's a story I won't soon forget.

8. "Silver Bells" - Jay Livingston and Ray Evans

There are plenty of great versions of this song, but I think the best ones come from the crooners: Dean Martin and Bing Crosby. The Dean Martin version is probably the most popular, and it certainly has a classic feel to it. The echoes of the choir are easily the best part of this version, with an almost hypnotic allure in their crescendo. The Bing Crosby version, a duet with Carol Richards, offers a sense of age that's not distracting. The duet really works well, with Carol Richards doing an especially good job. The harmonies meld together quite nicely.

"Silver Bells" is one of the best melodies of the holiday season. It might just be about the city, but it's a song that speaks to more of us than it really should. No matter where one is, "Silver Bells" is sure to leave a smile on one's face.

7. "White Christmas" - Irving Berlin

Instead, I think I'll talk about the doo wop version by the Drifters. While I've always been more a fan of the Ben E. King era Drifters as opposed to the Clyde McPhatter era Drifters, "White Christmas" is the one song from that era that I find that I enjoy the most. This version features two phenomenal performances from two very different singers: Bill Pinkney and Clyde McPhatter. McPhatter's incredibly light vocal oozes over the melody with an ease that very few soul singers have since been able to match; indeed, most covers of this version tend to have a girl sing the part in order to recreate this ease. But an even more underrated performance comes from Bill Pinkney; his excellent vocal shines through, crisp and clear. While it doesn't compare to the Bing Crosby original, it's a great song in its own right.

What more can I say? It's "White Christmas."

6. "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas" - Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane

Some songs sound great no matter who sings them. "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas" is one of those songs. It doesn't matter if one is listening to Judy Garland, Frank Sinatra, Michael Bublé, Sam Smith, Chrissie Hynde, etc. - this is just a spectacular piece of music. I can think of very few songs that more effectively combine past, present, and future than "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas." It seems to yearn for what is past while offering hopes for the future, all the while providing comfort in the present. It's one of those songs that compresses time, making it a truly modern piece of songwriting.

Of all the Christmas songs out there, "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas" is one of the most indicative of the season. Hearing this song from the window of a store truly evokes the spirit of Christmas, as a general spirit of goodwill seems to pour through this song's very soul. The progression of the harmonies combined with the gentle melody has a truly heartwarming effect. Lyrically, the song excels as well. "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas" is a song mainly about change, be it the simple passage of time or an alteration of circumstances. In spite of these changes, both family and Christmas endure.

By the same token, so does "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas" endure. It's one of the holiday classics that everyone seems to like. I have never met a person who dislikes "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas." I hope it stays that way.

5. "Peace on Earth/The Little Drummer Boy" - Katherine Kennicott Davis, Ian Fraser, Larry Grossman, and Alan Kohan

There's something truly magical about the song's introduction: I'm not sure if it's the simple piano melody melding perfectly into Bing and Bowie's harmonies, the subtle inclusion of the flute, or something else altogether. Even better is the actual vocal performance; neither Bing nor Bowie is exactly in time, yet they enter at exactly the same moment. There's a strong confidence to Bing's voice, despite him mostly singing in the background; all the while, Bowie's voice slips over the descant in excellent fashion. The bridge of this song might just be the best single moment in Christmas song history, with the strings and horns perfectly complementing the vocal climax.

Due to the strength of this song being its recording rather than the composition itself, it can't get any higher on the list. Yet there's no Christmas song that provides a more enjoyable listen. "Peace On Earth/The Little Drummer Boy" defies both time and genre to create a Christmas experience that is both unique and enjoyable.

4. "O Holy Night/Cantique de Noël"- Adolphe Adam

Unlike "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas," "O Holy Night" derives its strength from the performer rather than the composition itself (not that the composition is weak). While many, many pop stars - Whitney Houston, Bing Crosby, Mariah Carey - have all tried their hand at this piece, very few manage to do it justice. Of these, my favorite is probably Josh Groban's, what with him holding out the last F# so that it rings in the listener's ears. For the best versions, one has to look to classically trained singer. While the Joan Sutherland and Jussi Björling versions are more technically accomplished, I find myself more inclined towards the various duets featuring Luciano Pavarotti. While the other performances sound more supported, no doubt, Pavarotti and his various duet partners offer a true warmth that I find lacking in the most critically respected performances. My personal favorite is likely the duet between Pavarotti and fellow member of the Three Tenors, Placido Domingo. But there are plenty of duets, all of them great.

"O Holy Night" might be everyone's favorite Christmas song, but its overall sense of grandiosity keeps it out of the top three by just that much. Nonetheless, it's one of the best Christmas melodies ever, and it's quite possibly the most enjoyable Christmas song to listen to.

3. "Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!" - Jule Styne and Sammy Cahn

While not an explicit Christmas song, "Let It Snow" makes the list due to its being the most enjoyable holiday sing-along song of them all. No matter how much of a Grinch one might be, one simply must join in the chorus of this song. It matters not if one is in tune or even on pitch: the simple declaration of "Let It Snow" is enough to create a powerful musical sentiment. It's one of few songs in history that manages to succeed purely on the strength of its volume rather than its pure musicality. While this should theoretically drop it a few spots on this list, the reckless abandon of "Let It Snow" is actually much more indicative of the season than the precision of "O Holy Night" or "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas." It's the song that brings the community together.

"Let It Snow" is a work from Jule Styne, the same composer who wrote most of Broadway's most enduring hits, including "Don't Rain on My Parade" and "Everything's Coming Up Roses." "Let It Snow" fits perfectly into that canon, with a melody so catchy as to never go away. Yet at no point does "Let It Snow" ever become annoying or aggravating. It's got a pleasant enough bounce to keep the listener constantly engaged. And, unlike the similarly bouncy "Jingle Bells," "Let It Snow" has a nice, rich harmonic texture that rewards multiple listens. The line "O, I hate going out in the storm" gives me chills each time it is sung properly.

Considering that the similarly themed "Baby, It's Cold Outside" is one of the worst Christmas songs of all time, it's quite astonishing that "Let It Snow" would rank in the top three. Yet, unlike its "rape-y" contemporary, "Let It Snow" feels communal and consensual. It may be a romantic song that has little, if anything, to do with Christmas, but it creates a truly romantic Christmas atmosphere. It's the greatest Christmas sing-along song of them all, and I love hearing it every year.

2. "The Christmas Song" - Mel Tormé and Bob Wells

I love the 1961 version with Nat King Cole. It is an absolute classic. Yet, as good as it is, I think the various versions by the song's writer, Mel Tormé, are even better. As the cliché goes, the man had a voice like "buttah." The Velvet Fog's impeccable sense of melody works wonders in both the writing and the execution of Christmas song. In some ways, it's a jazz standard right up the Cole Porter line. In others, it's a timeless Christmas classic that isn't defined by any singular period of time. One thing is clear: whether it's Nat King Cole or Mel Tormé behind the microphone, this song sounds amazing.

Indeed, "The Christmas Song" is yet another one of those songs that manages to make the singer sound better by virtue of its very existence. Much like "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas," there isn't a truly bad version of "The Christmas Song" out there. It's a Christmas melody and sentiment so perfect that everyone can enjoy it. While the number one song is the best Christmas song of them all, "The Christmas Song" is a clear runner-up. It only loses the title due to there being an even better tune.

1. "Stille Nacht/Silent Night" - Franz Xaver Gruber

"Silent Night" is also one of few Christmas songs that works in nearly any setting. Be it a solo singer of classical or contemporary style, a choir, an orchestra, a folk group, "Silent Night" is the perfect closing song to any Christmas set. The melody and lyric are simple enough so that anyone can join into the song without it feeling interrupted. Its simplicity is its strength.

Unlike many people of my denomination, I'm not a stickler when it comes to reinforcing "the meaning of Christmas." The birth of Yeshua of Nazareth may be the main focus of the holiday season to many people, but I'm aware that said birth actually happened in the early autumn. Christmas just occurs on December 25th in order to coincide with the Roman celebration of Saturnalia. In spite of the arbitrary dating, though, I think there's a critical spirituality to the Christmas season that goes beyond both the simple giving of ourselves and the virtue of good-will towards man. Christmas is the time of year in which each human action is part of something greater, be it a sense of holiness or our joining in a "Parliament of Man" and/or "community of the world." Through its humility, "Silent Night" manages to capture that essential spirituality of Christmas that no other Christmas song has.

The first time I realized the genius of "Silent Night" was when I watched the Disney cash grab, Very Merry Christmas Songs, a straight-to-video sing-along set that used stock footage from older Disney movies in order to make a quick buck. Being young and not knowing any better, I watched the tape and enjoyed it fine enough. Watching the "Silent Night" segment, however, was one of my first moments of musical transcendence. While the Living Voices' version of the song isn't the best I've heard (it probably wouldn't even be in the top five), it carried a weight to it, at the time, that I'd never noticed before. It was a musical moment both glorious and humble. To this day, I still associate the imagery used in Fantasia's "Ave Maria" with "Silent Night" instead. In my opinion, it just fits better.

"Silent Night" is everything good and beautiful about Christmas. Be it a religious celebration of the Messiah's birth or a simple time of celebrating family and generosity, "Silent Night" carries the importance of the season within its very soul. Certainly, it is perhaps the simplest Christmas song of them all. But a brilliance hides behind that simplicity, a glow that can lead a Grinch's heart to grow three sizes. In my opinion, "Silent Night" isn't just the greatest Christmas song ever written; it's one of the best songs ever written, period.

I hope your day has been full of the hope and joy for mankind that makes December the most wondeful time of the year. May your families be happy and healthy, with good hopes for the year to come. Happy Holidays, and Merry Christmas!

Tuesday, November 18, 2014

Top Ten Reasons Why I Hate Death Note (And You Should, Too)

I have... problems with anime.

I can safely say that I've never seen an anime series that I can 100% recommend to anyone and everyone. Granted, I haven't seen Cowboy Bebop yet, but that's for another time. It's not for lack of good animation; goodness gracious, even the very worst anime puts most American cartoons to shame as far as animation is concerned. But, if the shows I've seen are representative of most anime, Japan seems to ascribe a certain ethos to anime that ends up complicating matters, to say the least. With most American animation, intention rarely goes beyond cheap humor or action. Anime is insistent upon delivering some kind of message, a characteristic that I wholeheartedly endorse. Yet not every message works...

Especially when said "message" is morally repugnant, insulting to human dignity, and hateful. Such is the message of Tetsugumi Obha's Death Note.

If my readers have not at least heard of Death Note, then I'll provide a brief history. Death Note is a manga series, written by Tetsugumi Obha, serialized in the shonen anime magazine, Weekly Shonen Jump. (For the record, shonen just means that said material is targeted for male viewers.) The series got popular enough that Madhouse Inc, one of the powerhouses of the shonen anime scene, decided to turn it into an anime. The series ran in America from 2007-2008, rapidly developing a cult following and becoming one of the most famous anime series in the Western world. The show revolves around a "Death Note," a book that has the ability to kill anyone and everyone whose name is written within its pages. A child prodigy named Light Yagami finds this Death Note and uses it to kill off the world's criminals. A battle of wits ensues between Light and L, an investigator who is trying to put an end to Light's murders.

I watched Death Note all the way through for three reasons. One: it has very good dialogue. I will grant it that. Two: it has a strong sense of suspense. Three: it is of sufficient esteem that it has become a central part of Japanese animation culture. Not watching Death Note, at the time of my viewing, felt like not watching The X-Files; it's not a series one can skip over if one wants to be well-versed in popular media. Now, I realize that Death Note is a terrible series that no one should watch; it has many, MANY deplorable elements preventing any critical viewer from possibly enjoying it. Critical acclaim or no, Death Note is a poorly conceived and created excuse for entertainment, an experience I wholeheartedly regret, an experience I hope to dissuade any other potential viewers from undergoing. I will be spoiling the ENTIRE anime in this top ten, so to further dissuade people from watching. If you decide to stop reading now and go watch the show, I cannot stop you. All I can say is that you are wasting precious hours you could be spending on something more valuable.

These are the top ten reasons I hate Death Note.

The above image is Death Note's animation at its very best. Keep in mind that Death Note has little, if anything, to do with tennis.

As far as pure artistry is concerned, Death Note has adequate background art and decent character designs. L, the only character in the show with any degree of good characterization, has a very interesting design, using massive eye size (relative to everyone else) in order to offer the illusion of inhumanity and social distance. The rest of the character models, though, leave a lot to be desired. Light Yagami is just a standard "good-looking" anime male, with none of his animation elements expanding upon the subtleties of his character. Of course, that would suggest that he has subtleties to his character, but, again, I digress.

The biggest problem with Death Note's animation is its lack of dynamism. There are only two times throughout the series where animation actually takes a real focus. First is the tennis match between Light Yagami and L, seen above. And then there are the death scenes, in which the animators kill various people with ludicrously pronounced heart attacks. It's a shame that all the good animation was wasted on such morbid material instead of creating interesting character dynamics. The rest of the time, it's just a bunch of talking heads doing talking head things. And, of course, Death Note falls victim to the classic anime trick of showing a still frame and then moving the camera up the frame in order to offer the illusion of animation when none is actually occurring. It's the cheapest move any animation company can do. Granted, Death Note is not as bad as some other anime when it comes to this, but it's still a disappointment.

To be fair, Death Note has some nice backgrounds and uses lighting competently. It's a shame that most of these elements are ruined by...

OK, look at the above image. That monster that looks like the lovechild of The Joker and Kefka from Final Fantasy VI is a Shinigami, the Grim Reapers of the Death Note universe. This one is eating an apple, a clear allusion to the importance of apples in both Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian religions. In both cases, it's a suggestion of sin and evil, be it the fruit from Eden's Tree of Life and/or Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil (there's still a debate as to whether or not there's two trees, but that's a subject for another blog) or the infamous Apple of Discord that kicked off the Trojan War. This is the most subtle symbol used in the entire show... and it has no bearing on the greater themes. Since the Shinigami is the one that eats the apple, there's no reflection on either Light or L. The apples have nothing to do with the humans, who, at the end of the day, are the only characters we are supposed to care about. Apples are never used to convey a greater point about a character's moral stature (in the animators' eyes at least). Thus, their symbolic value ends up tarnished.

The other symbols in the show, however, are much worse.

As one can clearly see, a heavenly light is shining upon Light. This means that he is being looked down upon from the heavens, equating him with a divine being. The only way one could get more overt with the symbolism would be to take Light and put him in front of a stained glass window.

I may have spoken too soon...

Last but not least, here's my "favorite" example of bad symbolism in the show.

See? Light has red hair, but L has blue hair. This means that they are opposites and have differing opinions on big issues like "justice." The two are bound to be enemies. The only way one couldn't understand this symbol is if one was comatose.

If a symbol is obvious or meaningless, it isn't worth inclusion. In fact, not including a symbol often forces the viewer to question whether there are symbols or not. Sometimes those symbols we discover that weren't even meant to be symbols are more meaningful than the most excruciatingly planned symbols in the creative process. Symbols should be used as subtle devices, not overt ones. In short, if Death Note wanted to be pure entertainment, it created half-assed symbols that only served to waste the viewer's time. If Death Note wanted to be "high art," then it failed to, formalistically, compare to the greater works that have come before it. Taking the first two issues into account, one can see why I dislike this show as a visual medium.

As for its status as an auditory medium...

First, let's address the background music for most of Death Note, the "murder" theme. You can find said music here. While this might sound impressive to many people, it really doesn't hold up to scrutiny. For one, the lyrics are just the "Dies Irae," once again offering the suggestion that Light is God. As noted before, this theme is obvious and meaningless. The choir is as standard as they come, but it suffers from having terrible enunciation. The entire piece is bloated and overblown, not using rhythm or harmony to accent any particular lyrical or thematic ideas. A final, though somewhat skeptical claim: this music's harmonic rhythm is frighteningly similar to the opening of Carl Orff's Carmina Burana, the go-to piece for making any subject matter sound more "epic." I wouldn't call the "murder" theme plagiarized, but I would call it unoriginal.

I cannot say the same for "L's Theme," which is so clearly based around Mike Oldfield's "Tubular Bells" that the song definitely feels plagiarized. The proof can be found in this cheaply made YouTube video, though I'd personally suggest playing the two songs side by side, using the original Mike Oldfield recording as opposed to The Exorcist remix that this YouTuber uses. "Light's Theme," on the other hand, is the best theme in the show, using the right mixture of King Crimson-inspired flange and piano to create a truly ominous ambience. This is the one song from Death Note that I would actually recommend people to seek out.

But the real reason this category exists is the opening theme music. Like most anime series, Death Note has a new opening theme for each season of the show. To give the first theme a bit of credit, the translation of the lyrics actually does relate to the show. Unfortunately, this is undermined by the needlessly bright and happy vocals. The song is too hyper to really evoke the main ambience of Death Note, a show that tries to be a grim neo-noir, aesthetically. The writers should have taken their cues from The X-Files or Law and Order before using this as the opening theme.

And then there's the second theme song.

I'd like to formulate a cogent criticism of this song, but just hearing it makes me want to stab myself in the face with a soddering iron. All I will say is that this is not an appropriate theme, musically or lyrically, to go with Death Note. It's loud, noisy, and unmusical; it's everything that's been wrong with heavy metal for the past fifteen years.

Granted, there's ending theme music as well. I didn't really listen to it, because I skipped to the next episode after one ended. I won't say these ending themes were bad, but I will say that terrible opening theme music incentivizes a viewer to not sit through the end credits. If you are so inclined, you can track these themes down, but I am not going to waste your or my time any further.

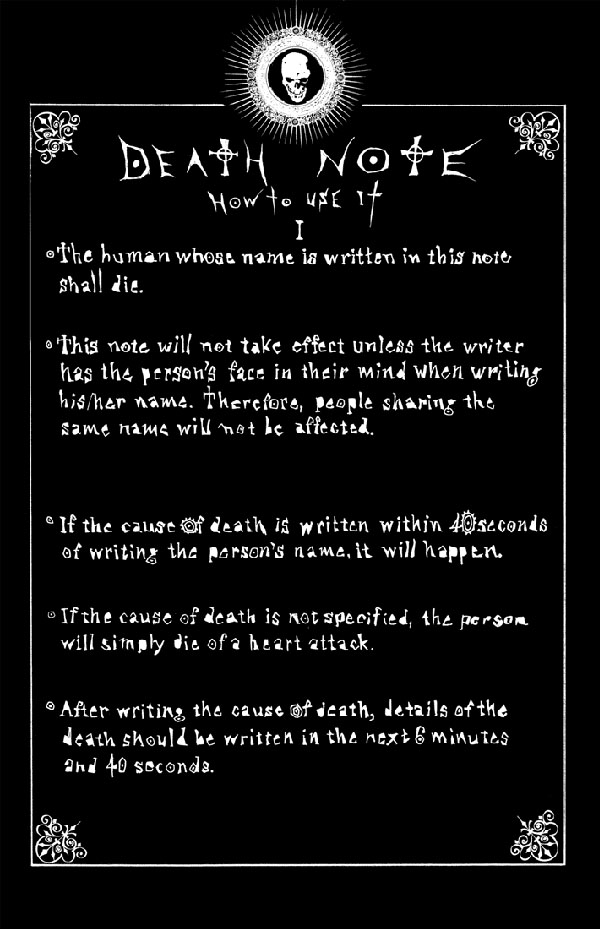

Number Seven

The Failure to Capitalize on the GOOD Elements of the Show

So, the above image details exactly how Death Note's main plot device works. The Death Note ensures the death of the victim so long as the user has the face and the name of a potential victim in mind. It has to be the victim's real name, so having an alias is the primary defense against death. To its credit, Death Note uses this rule to its fullest. They even expand upon this with the "Shinigami Eyes," which enable the user to learn someone else's name automatically but at the cost of half of one's remaining lifespan. This produces a lot of genuinely creative situations, allowing the show to use its ever flexible writing to its fullest.

But, if one looks at some of the other rules of the "Death Note," one realizes that there are so many other uses that this "Death Note" could have. For instance, "if the cause of death is written withen 40 seconds of writing the person's name, it will happen." Throughout the show's span, Death Note capitalizes upon this rule very few times, only two of which are creative whatsoever. As long as a death is within the laws of physics, the death can and will happen. Hit on the head with an anvil? OK. Impaled by a sword. Good to go. As long as the situation is feasible, the death can happen. The non-heart attack deaths that Death Note actually uses are relatively banal and dull. In my opinion, the show needed to take advantage of the opportunities its premise presented. The use of "more creative deaths" wouldn't only allow for some variety in the animation; it would allow the audience to see just how twisted and psychotic Light is becoming (more on that later). The show could even attempt some black comedy by killing off universally disliked characters in highly over-the-top and ludicrous ways.

To me, the failure to use the "Death Note" properly is a small but significant flaw in the grand scheme of the show. It might not be as glaring a problem as the weak music and animation, but it's ultimately a flaw that more drastically affects the plot, wherein we find most of Death Note's flaws. Including...

As I described above, most anime contain some kind of moral message or philosophy that they want to impart to the viewer. Often times, these messages are extremely complex and warrant multiple viewings. Fullmetal Alchemist's discussion of equality and humanity leads to some pretty poignant moments, as in the traumatic "Night of the Chimera's Cry." By the same token, Code: Geass offers some salient points on the nature of power and control, exploring the destructive tendencies of those who use these things to exploit others. What does Death Note have to offer?

"If you somehow get the capacity to kill large numbers of people, don't use it. It's wrong."

Thank you for pointing out the obvious, Death Note. Seriously, is this supposed to be the grand message of Death Note? For all its talk of "justice," the morality of Death Note is very black and white. Light is evil, the blood of his victims literally drawn onto his face. L and his allies are good; they might show sociopathic tendencies, but they are fighting for the good of mankind. There's nothing more to this moral; the decision is obvious to anyone who has a functioning mind. Where is the debate? Where is the complexity? Where is the non-obvious message? I can honestly learn more about the world through using my common sense than the message found in Death Note.

If one is to construe the theme to its most complex state, one could call Death Note a criticism of US actions against Japan during WWII, namely, the use of the atomic bomb. The argument: no one, no nation should ever have the capacity to wipe out so many people at once. While said message is strong in its conviction, it is ultimately shallow in its execution. We never see the complex motivations that go into the decision to use a weapon of mass destruction, nor do we see the real impact that it has on those who use it. Light gets the note, starts killing people, and that's that. He's never haunted by his decisions, nor does he ever experience any doubts. Likewise, L never loses faith in his convictions that what Light is doing is wrong (as he should). There's no mechanism by which the audience can really question the ethics of either side. One is obviously good. One is obviously evil. There is no grey. Thus, Death Note's message is tantamount to a basic lesson one could learn from an Aesop's fable. Hell, even one of Aesop's fables is more subtle with its theming than Death Note.

The key thing Death Note lacks is thematic sophistication. There's nothing really complex about it at all, despite what fans seem to say about it. And there's one other element of Death Note that is radically overhyped, one which I have even more problems with...

Many people dislike the ending of Death Note, saying it is wholly out of line with Light's character. Personally, the last episode of Death Note is actually one of the better ones. It's the only episode in which Light actually changes. He's been discovered. The "Death Note" is no longer in his possession. He does not know the real names of the people around him. He is well and truly trapped. It comes, then, as no surprise that he'd launch into a maniacal monologue about how he is the morally correct figure in all of this. It's the one time in Death Note that Light becomes the cheesy anime villain that we are hoping for. He laughs maniacally; he rants about moral absolutes to a crowd that does not accept his bull****. Moments like this are fun, and it feels honestly cathartic when Light is shot by the police for his many, many crimes against humanity.

There's the term "so bad, they're good" that we often ascribe to villains. While the very best villains are praised for their complex characterization, others are considered good purely on how much fun they have as villains. Light's greatest sin as a villain is his failure to enjoy himself. Unlike a Joker, a Kefka Palazzo, a Raul Silva, or a Lelouch vi Britannia, he does not take any pleasure in his evil. It's this stoicism that ultimately destroys his credibility as an antagonist we are supposed to like. He tries far too hard to be a god among men, ultimately becoming less interesting because of it.

The image you see above is my favorite character in Death Note, Mr. Aizawa. He's a slightly above average cop who manages to survive the events of the show, contributing to the investigation in small but meaningful ways. Most of his victories are either minor or Phyrric, but they are victories nonetheless. He fears for his family, but he's devoted to his work and actual justice. He has his moments of doubt, but he ultimately never loses his moral convictions. He's easily the most likeable character on the show, as he is arguably the most human figure in the entire anime.

It is unfortunate, then, that men like Aizawa end up constantly thrown to the side in this show. For Death Note seems to believe in the average man's inability to do anything against an übermensch. Aizawa and the other police officers stand no chance against Light; every time they try to outsmart him, they end up thwarted and humiliated. They need to have their own übermensch: L. Then, when L dies, he must be replaced by a different übermensch: Near. It's as if the forces of good and evil are wholly at the fingertips of the supermen and no one else. All the while, the "ordinary" characters in this show are regularly used as pawns; they have no free will, being used as mere pieces on a wei qui board.

Perhaps this is supposed to be a warning from Obha and the other creators of Death Note: the various übermensches in control of society's upper echelons are controlling us like puppets. It's a noble thought, but one that doesn't hold up to scrutiny. If Obha were trying to make that point, then he would have had Aizawa be the person that ultimately takes Light down, not Near. As it stands, Aizawa is the only Japanese investigator who ends up being half-competent. Even worse, when he seeks to do more, Near tells him no, as he's not smart enough to deal with Light. It's a complete smack to the face, as Aizawa has a competent intellect and a bravery that Near completely lacks. Near faces no consequences for carelessly discarding his most valuable asset, as he already has the ability to defeat Light with the help of his fellow übermensch, Mello. Such attitudes indicate that Aizawa and the other "normal" characters on the show are essentially useless and have no relevance to our story. They are background that, for all intents and purposes, should be ignored. By extension, in the real world, the average man should be ignored in favor of focusing on the conflict between supermen. They are the only ones that matter to Obha and the other creators of Death Note.

What I hate most about this theme is the insinuation that the average man has no role or significance in the broader universe. All the victories of Aizawa and the other investigators are inconsequential to Death Note's plot. However, in reality, the actions of the "average man" can end up reshaping the world. What can we say about the messenger who dropped General Robert E. Lee's battle plans at The Battle of Gettysburg? What of the man who stood in front of a line of tanks at Tiananmen Square? The man who fired the "shot heard round the world?" The various "average" civilians providing Twitter coverage of the Arab Spring? These "normal" people reshaped the world as we know it. As Tolstoy described, the universe is a network of infinite causes, and each major event that happens is the universe is the product of thousands of thousands of decisions. While chaos and complexity theory does offer mathematical insight as to the relative importance of some phenomena over others, one cannot deny that the smaller causes have, at the very least, some impact. For Obha and the creators of Death Note, the minor characters are completely insignificant to the narrative of the show. Ultimately, the attitude the show expresses towards the "average man" is disdainful and even somewhat hateful.

But, as much as Death Note hates men, that doesn't even come close to...

Some people who have read my other reviews and have watched Death Note with a critical eye knew this one was coming. Death Note is the most misogynistic, mainstream television series I have ever seen. Now, I am aware that this show targets a male audience, but that does not excuse its patronizing attitudes towards women. In addition, trust me when I say Death Note is misogynist and not sexist: a sexist show would just show women being inferior to men in some activity for another. No, Death Note actively hates women. The show only has two female characters with any relevance, but the two rank as some of my least favorite characters ever.

Meet Misa Amane, a character who...

I'm sorry. Did I call her a character? Let me start over.

Meet Misa AmaneTM, a sex object whom the animators and male characters throughout the series use to push the plot forward. Over the course of her object arc, Misa grows infatuated with Light after he murders the criminal who killed her parents. She acquires a Death Note of her own and starts killing other people who get in Light's way. Once she meets Light, though, she loses any and all agency. She is his eager slave, willing to do whatever he says without question. No matter what terrible thing she has to undergo, she emerges with the same wide-eyed adoration for Light. She might face death, rape, or both at the same time, but she doesn't care. So long as she has Light, nothing else matters. Not helping her objectification is the fact that Misa Amane is an utter airhead, unable to come up with any thought of her own. She is only able to manipulate others when Light guides her to do so. Her sex is used solely as a weapon, and her physical desire for Light has no value in the "relationship" whatsoever, as he dictates whenever she is to be "used."

Even worse is the treatment that the animators put her through. Misa is fan service incarnate, for the animators put her through almost every fetish one could possibly imagine. She dresses in a schoolgirl uniform, gothic leggings, pop star attire, a sexualized version of a nun's habit. Hell, there's even a scene in which Misa is in bondage. The animators were so desperate to win over viewers that they had Misa tied up and blindfolded in order to appeal to fans' perverted desires. Certainly, there's a plot related excuse for this animation, but one can create a plot contrivance for anything.

Also, to add a personal gripe to the mix, Misa has the most annoying voice I've ever heard, barring Chris Tucker. The Japanese voice acting sounds like a baby whining as much as humanly possible.

I've learned that Mr. Obha created Misa Amane in order to break up the monotony of an all-male cast. That should never be one's attitude when creating a character. Characters, men or women, need to feel like people. People have complex identities and motives. What is Misa's identity? A perfect servant for Light. What is Misa's motivation? Serving Light in whatever way possible. The creators do not treat Misa like a person. Her fanaticism combined with her stupidity make her practically inhuman in her devotion; for all intents and purposes, she is a robot, a tool used to satisfy the demands of Light and the plot.

It's easy to call Misa is the worst female character in the show, if not the worst character on the show period. But, being honest, there are times when I think the worst character on the show is actually the other female character: Kiyomi Takada. At the outset, Takada seems like the smarter counterpoint to Misa, an accomplice to Light that isn't a complete bimbo. She's smart, professional; she even holds a position of some authority as Light's chief supporter in the media. Yet, for all her exterior power, Takada is an even greater tool. She is even more emotionally dependent on Light than Misa, if that is even possible. Making matters worse, Light doesn't show any sign of affection for her whatsoever. At least he occasionally went on dates with Misa in order to make her happy; Takada has to be consoled with the false promise that Light will make her "the goddess of the new world." In the very worst part of her character arc, Takada is murdered in order to make sure Light's plan to take over the world is airtight.

In fact, killing and/or brutalizing women in order to enhance male character arcs is very much a constant throughout Death Note. Misa is forced to trade over half her life for the magical "Shinigami Eyes" ability twice during the show. Therefore, at most, she could live 25 years. But, not to worry, Misa need not fear that, as she commits suicide in the show's aftermath. All the women who try to capture Light end up dead, through one reason or another. Mello kidnaps Light's sister in order to coax him out of hiding. Even Light's mother doesn't come away from this show unscarred, as half her family ends up dying because of her son's actions. In the world of Death Note, women are just collateral damage, just bits of debris instead of human beings.

It's quite astonishing that a show of such acclaim as Death Note manages to uphold its reputation despite the hundreds of misogynist moments and concepts contained within it. The women of Death Note are weak, shallow, stupid, annoying, useless, male-dependent, rag dolls who only gain value once they are murdered, very often by their own hands. If that's not indicative of a deep hatred of women, I don't know what is.

And, the worst part? That's not even number one.

Death Note's biggest crime is not the number of murders within it. There are plenty of great works of art that feature disgusting amounts of gore and violence (The Triumph of Death, most of the works of Haruki Murakami, Pulp Fiction). Death Note's biggest crime is claiming that these murders are permissible or "part of a greater good." Death Note believes that Light is the good guy and that we should side with him.

Many readers might be skeptical of this assertion. Is not Light considered one of the best villains in anime (if falsely)? Therefore, how can he possibly be considered a good person on the show? Well, herein comes the matter of Death Note's framing. For the vast majority of the show, Light never indulges in the attitudes that one would expect of a villain. As I said before, this significantly impedes his development as an antagonist. It makes him a formulaic, static character. But such a depiction also indicates that Light is becoming numb to his murders. As he kills more and more people, it becomes more of a day job than an expunging the world of his enemies. There have been plenty of other people who were numb to mass murders. Such people include this one:

This one:

And, let's not forget, this one:

Yes, Light Yagami is as evil as Adolf Hitler. In fact, Light/Kira kills almost as many people (offscreen) as did the Nazis. When depicting the stories of genocidal maniacs and serial killers, any effort to humanize the evil must clearly be used to illustrate why said evil exists. Also, such a depiction should never cast the villainous person in a positive light. To make the point clear, Der Untergang (Downfall), a film that I consider to be one of the best movies of the 21st century, received tremendous criticism for so much as remotely humanizing Hitler. I've discussed why Bruno Ganz's depiction isn't unethical in my review of the film, but the criticism has, at the least, some merit. We shouldn't, as ethical agents, portray genocidal maniacs as "good" people.

Death Note doesn't just frame Light as a good person; Death Note frames Light as a God among men. Take a look at his death, for instance.

This is not the death of someone who is being damned. This is the death of someone who is being lifted up to a godlike status. Light's face is utterly at peace, despite his murdering hundreds of thousands of people. Throughout Death Note's last episode, Light stumbles around with heavenly light constantly shining upon him, as if he is a Christ-like figure in his pursuit to free the world of crime. Everyone else has simply failed to understand him and his "good intentions." As he dies surrounded in the heavenly glow, we are meant to look at him with an attitude of lament, as if the world's hope for salvation from sin has died. Light's death isn't the only moment in which this happens. At various points throughout the show, Light is equated with God and/or heaven. Light surrounds Light. Light is never wholly shown as the bad guy, as the show always offers the suggestion that his concept of "justice" is the right one. The show offers us a choice in whom we can side with. It may be my personal morality clouding my critical judgment, but I feel so much as offering the choice to follow a genocidal maniac is an action that is morally questionable at the very least.

It's not the murders that sickens me; it's not Light's boring character; it's the fact that the animators send the viewers an implicit message that is morally wrong under any grounded moral theory in human existence. Kant wouldn't stand for this. Bentham wouldn't stand for this. Nietzsche wouldn't stand for this. Moses wouldn't stand for this. Yeshua of Nazareth wouldn't stand for this. Muhammad wouldn't stand for this. Siddhartha Gautama wouldn't stand for this. No moral person would condone the adoration of a serial killer. Yet Death Note does.

Perhaps some of my readers think I am looking too deeply into this matter. After all, my claim that Death Note supports Light is based on a background cue and a Longinan concept of formalism (props to you if you know what this last term means). Indeed, even if one accepts my terms, there could be a counter-argument. Maybe Death Note is trying to say that anyone with power over life and death is evil, including God himself. I do not subscribe to this theory for two reasons. One: there is a difference between letting someone die within a world that is predetermined by human free will and action and actively killing someone. Two: if this was the grand plan of Death Note, and if this was the real message Death Note was trying to send, then Obha and the other creators would have made it more explicit. Even if I were to agree with this theory, I could then only recommend Death Note to atheists. As it stands, I cannot recommend Death Note to anyone.

If one needed any proof to show that my theory about Death Note's celebration of murder is correct, one only needs to look at Death Note's fanbase. Just a quick check on YouTube gives us plenty of fan theories of "how Light should have won" or "Death Note's ending sucks because Light lost." There were people who tuned into Death Note wanting Light to win. There are fan sites praising Light as the "God of the New World" that he wants to be. There are people who have adopted his same concept of "kill every criminal who has ever committed any crime ever" mentality. "Light Yagamists," as I like to call them, are some of the most frightening fans I have ever witnessed. In a fanatic fashion, they are praising a serial killer as the paragon of human morality.

The very fact that "Light Yagmists" exist indicates that Death Note fails to do its job. Whenever a villain, whenever a truly terrible person is the focus of a show and/or movie, they must be framed as if their actions are wrong. Consider Michael Corleone of The Godfather. He might have elements we can sympathize with, but at no point do we ever think that his actions are moral. The same goes for Tyler Durden, Norman Bates, or the Joker. We are not supposed to admire these people. Yet people do, and the heavy-handedness of Death Note's imagery and morality leads them to whole-heartedly follow their fandom. People who cosplay as the Joker and Harley Quinn say that they wouldn't ever kill someone with lethal laughing gas; people who are fans of Light Yagami say they would use the "Death Note" if one existed in real life. This is in spite of the fact that Death Note should clearly show that no human being should ever want to use the "Death Note." In fact, the "Death Note" ranked as the second-most desired fictional ability in anime in this, popularity-determined WatchMojo countdown; if that isn't a massive moral failing on the creators' part, I don't know what is. The "Death Note" has one function: murder. The fact that people want this power is indelible proof that the show, inadvertently or otherwise, endorses it.

_________________________________________________________________________________

If my ramblings and rankings haven't made the point clear enough. I think Death Note isn't just a bad show. It's an evil show. In spite of good dialogue and appropriate suspense, it promotes a morality that I find wholly repugnant. When watching it, I didn't fully see its flaws. But, after just one day of thinking it over, I realized that this show was quite possibly the worst I had ever seen. Death Note is a waste of time, of paper, of oxygen. It is a show that is lazily produced and paced. It is a show with a clear lack of focus. It is a show that espouses disgusting morals through insidious devices. I do not give traditional ratings and/or recommendations to television series on this blog. This feels appropriate for a show like Death Note, a show that is practically a vacuum in its spiritual emptiness.

I hate this show. So should you.

I can safely say that I've never seen an anime series that I can 100% recommend to anyone and everyone. Granted, I haven't seen Cowboy Bebop yet, but that's for another time. It's not for lack of good animation; goodness gracious, even the very worst anime puts most American cartoons to shame as far as animation is concerned. But, if the shows I've seen are representative of most anime, Japan seems to ascribe a certain ethos to anime that ends up complicating matters, to say the least. With most American animation, intention rarely goes beyond cheap humor or action. Anime is insistent upon delivering some kind of message, a characteristic that I wholeheartedly endorse. Yet not every message works...

Especially when said "message" is morally repugnant, insulting to human dignity, and hateful. Such is the message of Tetsugumi Obha's Death Note.

If my readers have not at least heard of Death Note, then I'll provide a brief history. Death Note is a manga series, written by Tetsugumi Obha, serialized in the shonen anime magazine, Weekly Shonen Jump. (For the record, shonen just means that said material is targeted for male viewers.) The series got popular enough that Madhouse Inc, one of the powerhouses of the shonen anime scene, decided to turn it into an anime. The series ran in America from 2007-2008, rapidly developing a cult following and becoming one of the most famous anime series in the Western world. The show revolves around a "Death Note," a book that has the ability to kill anyone and everyone whose name is written within its pages. A child prodigy named Light Yagami finds this Death Note and uses it to kill off the world's criminals. A battle of wits ensues between Light and L, an investigator who is trying to put an end to Light's murders.

I watched Death Note all the way through for three reasons. One: it has very good dialogue. I will grant it that. Two: it has a strong sense of suspense. Three: it is of sufficient esteem that it has become a central part of Japanese animation culture. Not watching Death Note, at the time of my viewing, felt like not watching The X-Files; it's not a series one can skip over if one wants to be well-versed in popular media. Now, I realize that Death Note is a terrible series that no one should watch; it has many, MANY deplorable elements preventing any critical viewer from possibly enjoying it. Critical acclaim or no, Death Note is a poorly conceived and created excuse for entertainment, an experience I wholeheartedly regret, an experience I hope to dissuade any other potential viewers from undergoing. I will be spoiling the ENTIRE anime in this top ten, so to further dissuade people from watching. If you decide to stop reading now and go watch the show, I cannot stop you. All I can say is that you are wasting precious hours you could be spending on something more valuable.

These are the top ten reasons I hate Death Note.

Number Ten

The BORING AnimationThe above image is Death Note's animation at its very best. Keep in mind that Death Note has little, if anything, to do with tennis.

As far as pure artistry is concerned, Death Note has adequate background art and decent character designs. L, the only character in the show with any degree of good characterization, has a very interesting design, using massive eye size (relative to everyone else) in order to offer the illusion of inhumanity and social distance. The rest of the character models, though, leave a lot to be desired. Light Yagami is just a standard "good-looking" anime male, with none of his animation elements expanding upon the subtleties of his character. Of course, that would suggest that he has subtleties to his character, but, again, I digress.

|

| The last time I checked, people don't stick their tongues out when they're having a heart attack. |

To be fair, Death Note has some nice backgrounds and uses lighting competently. It's a shame that most of these elements are ruined by...

Number Nine

The OBVIOUS and/or MEANINGLESS SymbolismOK, look at the above image. That monster that looks like the lovechild of The Joker and Kefka from Final Fantasy VI is a Shinigami, the Grim Reapers of the Death Note universe. This one is eating an apple, a clear allusion to the importance of apples in both Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian religions. In both cases, it's a suggestion of sin and evil, be it the fruit from Eden's Tree of Life and/or Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil (there's still a debate as to whether or not there's two trees, but that's a subject for another blog) or the infamous Apple of Discord that kicked off the Trojan War. This is the most subtle symbol used in the entire show... and it has no bearing on the greater themes. Since the Shinigami is the one that eats the apple, there's no reflection on either Light or L. The apples have nothing to do with the humans, who, at the end of the day, are the only characters we are supposed to care about. Apples are never used to convey a greater point about a character's moral stature (in the animators' eyes at least). Thus, their symbolic value ends up tarnished.

The other symbols in the show, however, are much worse.

As one can clearly see, a heavenly light is shining upon Light. This means that he is being looked down upon from the heavens, equating him with a divine being. The only way one could get more overt with the symbolism would be to take Light and put him in front of a stained glass window.

I may have spoken too soon...

Last but not least, here's my "favorite" example of bad symbolism in the show.

See? Light has red hair, but L has blue hair. This means that they are opposites and have differing opinions on big issues like "justice." The two are bound to be enemies. The only way one couldn't understand this symbol is if one was comatose.